Protect whistleblowers now

Only 7 out of Africa’s 54 countries have passed whistleblower protection laws. This is despite the UN Convention Corruption (UNCAC), in Article 33, calling on governments to introduce measures to provide protection for ‘reporting persons’.

This continental tardiness in introducing laws is compounded by the fact some countries do not implement the laws they pass while others do so half-heartedly and ineffectively.

Take Namibia for example, where a Whistleblower Protection Act was passed in 2017 but five years later there is no sign of it becoming operational. Officially, the Namibian government cites financial constraints as the reason for not setting a Whistleblower Protection Office, but there also seems to be a reluctance among top politicians to put into action an agency that could open more cans of worms.

In South Africa the recent Zondo Commission report called for improved protections for whistleblowers even though the country has had a less-than-effective Protected Disclosures Act in place since 2000.

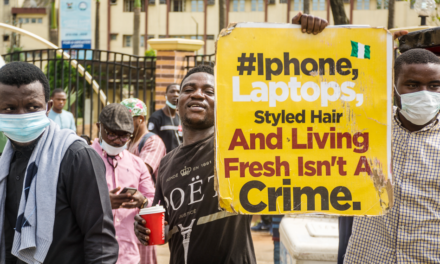

Ironically, this extremely patchy record across Africa comes at a time when the importance and value of the whistleblower in exposing corruption and other wrongdoings has never been clearer.

Whistleblowers play a crucial role in uncovering mismanagement, fraud and corruption. Their actions can result in the detection of serious crime and misconduct, the recovery of stolen resources, and the prevention of serious harm including the saving of lives.

Namibia’s worst corruption scandal since independence in 1990 – known as ‘Fishrot’ – would have never come to light if not for the brave actions of Icelander Johannes Stefansson who ensured key evidence got into the hands of Wikileaks and the international media. Fishrot sparked national outrage in Namibia and within a week of its exposure in The Namibian newspaper and Icelandic media two members of Cabinet were arrested and in jail. The scandal centered on an Icelandic fishing company, Samherji, which allegedly bribed Namibian ministers, officials, and businessmen to obtain access to most of the country’s horse mackerel quotas over a period of seven years.

Bianca Goodson and Athol Williams made important revelations about state capture in South Africa which are slowly leading to crucial changes in business and political cultures.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), bank officials Gradi Koko Lobanga and Navy Malela exposed a global money laundering network linked to an Israeli mining magnate.

But all have also suffered. There was an attempt to poison Stefansson in Cape Town, Goodson lost her job and faced other traumas, Williams had to go into exile in fear for his life, while Lobanga and Malela who fled to Europe were sentenced to death in absentia.

And, lest we forget, whistleblowing can also be deadly. Whistleblower Babita Deokaran was gunned down outside her home in August 2021 near Johannesburg. As a senior finance official in the Gauteng Provincial Government Department of Healthh she had repeatedly reported cases of corruption.

As can be seen from these examples, whistleblowers can take tremendous risks for the greater good for the sake of their societies and increasingly global good governance.

In Namibia, my own organisation – the Institute for Public Policy Research – is about to launch an online whistleblower protection platform. This is part of a new IPPR project called Integrity Namibia which seeks to build a national alliance against corruption in the next three years.

We are busy learning from already great examples on the continent like the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa (PPLAAF) and Corruption Watch in South Africa. We are looking at picking up tips on how to ensure the platform is secure, but perhaps more importantly how reports can be followed up effectively in a situation where there is public distrust in institutions like the Anti-Corruption Commission. This will mean close cooperation with Namibia’s independent media is required. Follow-ups on reports will only be done with the agreement of the whistleblower.

While civil society initiatives are not substitutes for effective whistleblower protection laws, they can help to provide an avenue for those who want to report wrongdoing as well as give advice and support. They must also ensure confidentiality and security when receiving whistleblower’s reports.

Since starting to speak out about the need to do much more to protect whistleblowers, I’ve received disturbing reports about whistleblowers who have been physically attacked, threatened, and harassed in Namibia. None of these cases were reported in the media and the whistleblowers are frustrated at the lack of action in response to their reporting, as they remain isolated, and still under threat. Ultimately, only an operational whistleblower law will ensure protection but, in the meantime, civil society can provide legal and psycho-social support and possibly, if funding can be found, to compensate whistleblowers who have lost their jobs.

It’s a much-quoted cliché that ‘evil thrives when good people do nothing’ but it remains as relevant as ever. The corrupt flourish in atmospheres of secrecy and impunity. They have to be exposed and called to account. The whistleblowers who do this work deserve our respect and protection. We must do all we can to protect whistleblowers now.

Bernhard Esau, Sacky Shanghala, Tamson Hatuikulipi, James Hatuikulipi, and businessmen Ricardo Gustavo, Pius Mwatelulo – have been in custody since November 2019.