African struggles were and still are struggles for transparency and informed participation

Secrecy was a weapon used by colonial administrations so they could govern without impactful challenges by the African populations they were suppressing. Thus, they established legislation to ensure that local officers working for them did not disclose information that could potentially trigger a challenge to their administrations.

In many respects struggles for independence in Africa were also struggles for transparency and informed participation. That’s no surprise. After all, access to information is intended to inform and empower participation and expression in a democratic process.

In democratic processes, when citizens receive information or fail to receive information, they are expected to express themselves on either the contents of the information they receive or the failure to receive such public information. Unfortunately, several African governments restrict these liberties, failing the intention of citizens accessing public information.

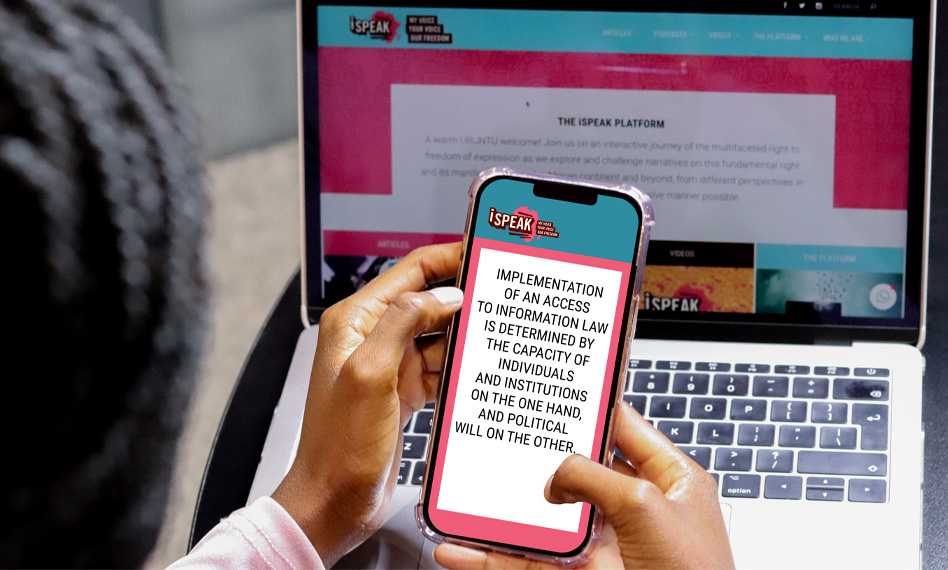

Over the years, the Africa Freedom of Information Centre (AFIC), through its body of work and research, has realised that implementation of an access to information law is determined by the capacity of individuals and institutions, on the one hand, and political will on the other.

Seven years after the adoption of the Access to Information Act in Uganda, government agencies frequently refused to grant access to requested information. This goes hand in hand with the low level of demand for information requests owing to low levels of uptake by citizens.

Over the last few years there has been a considerable shift as the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), develops a strong policy framework to strengthen the right of the public to gain access to information, as well as an insistent demand for proactive disclosure of information, held by public and corporate bodies with relevant public information deemed necessary for the public.

At a continental level, a strong policy framework is being established that strengthens rights of the public to gain access to information that is their right.

Through its treaties – the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, African Charter on the Values and Principles of Public Service Administration, African Youth Charter and the African Statistics Charter – the African Union underscores the value of public access to information in addressing Africa’s development challenges, and positioning the continent on the highway to development.

Incentives and sanctions determine the extent to which a piece of legislation can be implemented. Incentives can include training and awareness raising of officials responsible for implementation, facilitating them with appropriate equipment and tools, clarifying roles and responsibilities, appraising officers on specific obligations prescribed within the law and applying a rewards system for better performance of assigned roles.

Rewards may include official recognition for performance, opportunities for training, prizes, promotion, etc. On the other hand, an effective sanctions regime requires the establishment of a clear mechanism determining compliance and appropriate reprimands for failure. This may include caution, suspension, demotion, dismissal or other forms of reprimand. Beyond incentives and sanctions at an individual officer level, it is critical that the same applies at the broader institutional level.

Effective implementation of ATI laws involves establishment of procedures for the agency to follow in receiving and responding to information requests, proactively disclosing information, allocating personnel, and providing equipment to support implementation, improving records management and ensuing timeliness in responding to information requests. Political will thus goes beyond receiving and responding to information requests, to creating the necessary capacity and support environment for effective implementation of laws.

AFIC conducted training for public officials and CSOs in four of Uganda’s districts. Twelve weeks after the initial training follow-up workshops were held to obtain feedback on how participants had used knowledge obtained from the training. Results revealed that there was increased demand for information and improved responsiveness by respective government agencies. One the side of civil society, at least 3 in every four participants that attend had filed an information request and 71% of these requests had been responded to by respective agencies. Our conclusion from these findings was that capacity of citizens and of public servants was critical in fostering implementation of the Access to Information Act.

Capacity alone is not sufficient. Examination of information requests and feedback revealed that despite understanding the law and information requests being properly filed, some agencies would not respond to certain requests especially where significant breach of accountability or procedures was suspected, raising concerns around political will.

It should be understood that access to information laws aim to compel officials to disclose information they otherwise would not reveal because of one reason or the other. Thus, successful implementation also requires enforcement by a mechanism that is external to the body to which information requests are filed that is independent, accessible and affordable by citizens.

Through the Model Law on Access to Information for African Union Member States, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights recommends that access to information oversight bodies should be legally established and mandated to, among others, monitor and regulate implementation by public and covered private bodies, hear appeals, audit compliance, receive annual reports from MDAs, impose fines for non-compliance, promote public awareness, make annual reports and provide advice on how to strengthen the advancement of the right to information in respective countries.

In Africa, oversight and enforcement of access to information laws is by different entities ranging from national human rights institutions (Guinea), ombudsman (Ethiopia, Niger and Rwanda), attorney general (Nigeria), parliament (Uganda), monitoring commission (Angola) independent information commissioners (Liberia, South Sudan, Sierra Leone) and information regulator in South Africa.

Irrespective of the name of institution or agency where the oversight mandate lies, the need for resources and capacity by respective RTI oversight authorities is critical across the board.

In Liberia, two years after the establishment of the Information Commission, Centre for Media Studies and Peace Building (CEMESP) filed an appeal to the Country’s Independent Information Commission. The Commission declined to hear the appeal on account of lack of funds. CEMESP then filed an appeal to the Supreme Court which in turn ruled against the Information Commission. It is thus not enough to have an oversight mechanism in law. It should be independent, capacitated and prepared to play its role

Indeed, all right to information oversight agencies across Africa face challenges of one form or the other. Reporting to parliament is one of the opportunities available for these bodies to engage on addressing their challenges. The Sierra Leone Information Commission as well as the South African Human Rights Commission effectively used this platform to explain the importance of their oversight role, shine light on agencies that don’t comply with RTI obligations and highlight resource needs of these information commissions.

In an agency, people especially junior officers see their seniors breach the law or abuse their positions. Whereas many access to information laws in Africa expressly state that individuals disclosing information about such breaches are protected, in practice this has been a challenge. This greatly undermines the realisation of access to information goals.