What I learnt from the Mauritius/FinCEN/Pandora leaks

It was early 2019 when my then supervisor and managing editor for content, at the Daily Monitor, Tabu Butagira, now the newspaper’s managing editor, brought me onto to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) initiative as their correspondent in Uganda.

The first assignment was impromptu. The ICIJ’s coordinator for partnerships in Africa and the Middle East, Will Fitzgibbon, had flown into the country to thrash out details of a new project – the Mauritius Leaks – when Mr Butagira looped me into the meeting.

The Mauritius Leaks was a cross-border investigation project into how one law firm in the east African island nation of Mauritius helped companies leach tax revenue from poor African, Arab, and Asian nations.

Over the years, the ICIJ has partnered with specific media outlets on the African continent to work with individual journalists on major investigative cross border investigations such as the Mauritius Leaks, the Panama and Pandora Papers, and the Luanda Leaks. The ICIJ also publishes work of journalists from Africa on its website.

With my ten years’ experience as a journalist, covering diverse beats from politics to oil/gas, public affairs, business and finance, environment to investigations, among others, I accepted the challenge. It was both thrilling and tense at the same time, having seen the previous reporting projects.

I like to say that I have been beaten and battered by the trade, including being fired twice over stories related to powerful corporations who were among top advertisers at the time. When firing me, the publisher’s parting advice was: “we have to strike a balance because we have to survive.” But like the saying goes: ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’; so that’s when I started developing a thick skin.

Most of my previous investigative body of work centered on government agencies, corruption in general terms, and public policy misadventures, among others, but not so much about individuals.

This was essentially a new challenge, and a monumental one for that matter. If there is any story project that required digging deep into large files and raw data, it is the ICIJ project. First, are the series of planning meetings with the ICIJ coordinators in Washington and other journalists from the region. Then more meetings to crystallise the story idea and finally into execution. The Covid-19 pandemic that made a landfall in 2020 upended the meetings and we went online.

The process of sifting through data is intense, tedious and there is also an air of expectancy – what will you find? What will be a front page/viral story?

Journalists in other territories/countries help to chase around information such as individual profiles, company registration documents, simple fact files, due diligence, among others, when needed from elsewhere. It also means keeping in touch individually, or through the ICIJ teams in Washington. Of course, it comes with its own challenges such as having to chase around people on both ends. Email is our most effective means of communication.

After two or so meetings with the ICIJ team, and a great deal of rummaging through the data, the results on Uganda returned one prominent person – billed as one of the richest men in the country – with investments in real estate, leisure and hospitality, and energy.

So together with Will, we drove to his only known investment in energy, a thermal plant, located 210km east of the capital, Kampala, for a stakeout. As we drove back, Will gave me a full picture of the assignment – and of course the main point of the investigation – to find further evidence backing up the information we had found and the claims we were going to make in our story.

According to the Mauritius Leaks, the businessman in question benefited from an energy investment amounting to $17.5m – structured in Mauritius and which, according to tax analysts, smacked of “a deliberate aggressive tax planning” which would benefit from the Double Taxation Agreement between the Indian Ocean Island nation and Uganda.

Besides being ICIJ’s point man in Kampala, I was to also work discreetly to minimise possible leaks and also make sure that the story was not compromised in any way. After sharing experiences with fellow colleagues in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, South Sudan, DR Congo, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Ghana, Ethiopia, Senegal, and Nigeria, it is not hard to imagine why certain assignments must and should be kept discreet.

The newsroom itself can be a point of corruption – after all we are beings. There is a lot of wheeling and dealing amongst colleagues: by beat reporters, editors, and newsroom managers generally. These betrayals come in many forms. I can recall how I have been double-crossed a few times on co-shared assignments. In one instance my colleague I was working with, informed the subject about the story we were piecing together and that was about to come out. He used that information to seek financial inducement to stop its publication.

I learnt my lesson and so I put measures in place to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

Closer towards publication of the Mauritius Leaks story, an executive of the businessman’s called for a face to face meeting to explain that things—the transaction of the offshore dealing—had not worked according to plan, so it was pointless publishing the story. He offered $1,383 to drop the story. I have been through such temptations so I know how to wiggle out. Taking the money meant me walking away from the story project and perhaps ICIJ itself.

After publication of the story on the front cover the company threatened to sue but dropped the matter eventually.

It was, as usual, a tense moment.

I have learnt over the years that after p*****g off people, one has to lie low for a few days, even a week, while the story is in the spotlight. I recall being invited by a colleague to appear on a television morning show the next day to talk about the story but I didn’t, and I make it a practice not to. Even as a television journalist I try to keep a very low profile.

Before publication of the Mauritius Leaks story I was overthinking many issues – would my story be sidelined in consideration of commercial interests, as was the case in many instances I can cite. At the same time I was comforted by the fact that the newspaper I work for has some pretty solid checks and balances.

Perhaps I should also add that both the newspaper and myself, enjoy unfettered editorial independence to write about any subject and any person, so long as there’s a prima facie case. Of course, there have always been exceptions and we all have our bad days.

The second story project I worked on in 2019 was the FinCen Files aka Project Cassandra. We held the first planning meeting for the project in Hamburg, Germany, on the sidelines of the international global investigations conference in September that year. The meeting was attended by more than 100 journalists from all over the world. We never met again physically due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

For journalists in Sub-Saharan Africa extended by the pandemic and its associated effects including lockdowns and shrinking businesses, ICIJ and CENOZO, offered a small financial grant to facilitate individual journalists to progress with the story. We published the stories in September 2020 but were mostly crowded out by the growing embers of Covid-19. There wasn’t anything significant on Uganda, so I didn’t write anything.

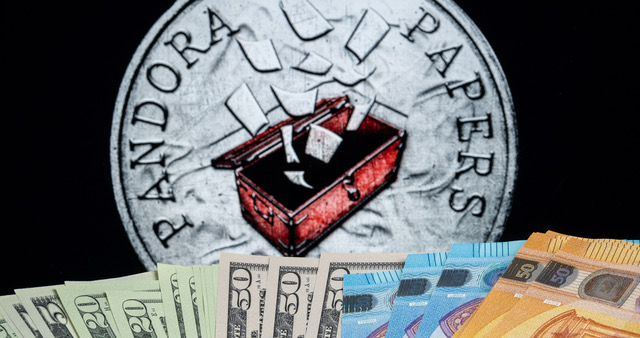

The third story project was last year; the Pandora Papers, focusing on offshore dealings. The leaks – a mix of spreadsheets, tax declarations, invoices, PowerPoint presentations, emails and company records listing directors and shareholders, detailed how the world’s ultra-wealthy, politicians, lawyers, and the global elite used 14 offshore service providers to either secretly own property or move wealth around in a dozen jurisdictions to avoid tax.

Planning for the Pandora Paper started in early 2021 with a series of online meetings held by the ICIJ teams sequestered in their homes around the world. Of all three projects I think this was the most hair-raising. It contained a number of sacred cows—individuals and companies—which put myself, and the newspaper in a situation where it was critical that we remain vigilant and exercise extreme caution. In fact, five companies threatened to sue if I wrote about them. They claimed their transactions were not in any way illegal in the jurisdictions they happened in, so presenting them in anyway could be impugned by the public as involved in wrongdoing. Well, no one sued eventually.

Journalism, we like to tell ourselves is about causing impact. Not so much in Uganda, as elsewhere in Africa. While the three-story projects reverberated in other territories, this wasn’t the case in Uganda. Part of the reason is the corrupt deep state system we operate in. The second and more concerning explanation is that people are no longer startled by corruption and related money laundering stories no matter how big they are.

For many journalists, including myself, this lack or cause for little change, is a source of pent-up frustration sometimes.