Digital authoritarians attack African online spaces

The ether is alive with the sounds of youth demands and activism.

But the old-guard are digging in, using every means at their disposal to quell the demand for change on the part of those they perceive to be an unruly cohort of disrespectful young ones.

Digital authoritarianism has become the worrying and defining trait of many African governments’ responses to growing digital civic mobilisation and online activism across the continent.

But as the groundswell of demands for a better, more inclusive Africa have increased, so too have the repressive practices and tendencies of a number of African governments been coming increasingly to the fore.

In March 2021, the Nigeria-based Paradigm Initiative reported that from 2016 to 2017, 22 African governments have ordered internet disruptions or shutdowns. Aside from the human rights violations, these have cost their countries tens of millions of dollars in lost economic activity at a time when African leaders have been touting the socio-economic promises of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

This increased use of repressive tactics has coincided with the rising tide of youth activism and protests across the continent over the last decade.

Caught up in the repression and online silencing are not just youthful agitators, but also journalists and civil society actors, both sectors that numerous African governments and leaders have long considered a threat to their absolute command and control of their societies.

A February 2021 report, titled ‘Digital Rights in Closing Civic Space: Lessons from Ten African Countries’, by the UK-based Institute of Development Studies noted that the “five tactics used most often to close online civic space in Africa are digital surveillance, disinformation, internet shutdowns, legislation, and arrests for online speech”.

Criminalised communication

To justify the deployment of such repressive tactics, governments have been using youth radicalisation as an excuse, among others. This scare narrative is largely a consequence and legacy of the war on terror that was globalised in the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the US.

Since about 2010, cybersecurity and cybercrime have become significant locus and focus areas of this terror narrative, as African youth, media and civil society have gone online in increasing numbers and as the influence of social media has become ever more pronounced in African civic life.

In tandem, digital surveillance and restrictive social media regulations have become ever-present and disturbing realities for many Africans.

Surveillance concerns have been heightened as reports emerged over the last decade of various African countries having purchased and deployed sophisticated communications and digital surveillance technologies.

Similarly, over the last decade or so, most African countries have, as part of their cybercrime measures, enacted SIM card registration regimes, that have become central to state surveillance efforts in the digital age, which in Africa is experienced primarily via mobile phones.

In 2019 Privacy International reported that 50 African countries had implemented SIM card registration regulations, while only Cabo Verde and the Comores did not have laws or intentions to create such laws. In two other countries – Namibia and Djibouti – the issue of SIM card registrations remained unresolved.

Privacy International stated that “while governments justify mandatory SIM card registration laws on the grounds that they assist in preventing and detecting crime, “there is no convincing empirical evidence that mandatory registration in fact systematically lowers crime rates,” and “no robust empirical studies that show that such measures make a difference in terms of crime detection.”

On top of this, cybercrime laws – from Nigeria to Egypt – have also used vague language to criminalise some forms of online expression. Since 2015/16 countries, from Benin to Tanzania, have used or introduced social media regulations that effectively served the same purpose.

Prompted by these concerns, UN Special Rapporteur on free expression, David Kaye, stated in a 2018 report: “Broadly worded restrictive laws on “extremism”, blasphemy, defamation, “offensive” speech, “false news” and “propaganda” often serve as pretexts for demanding that telecommunications companies suppress legitimate discourse.”

Shrinking space

The logical consequence of all of this has been a shrinking of African civic space, both offline and online, over recent years.

In its 2020 report on the state of civic space, global civil society monitor CIVICUS found that out of the 49 African countries monitored only two – Cabo Verde and Sao Tome and Principe – displayed open civic spaces.

African governments have increasingly been using violence, intimidation and harassment to counter youth protests as well as arresting journalists who cover such protests, which is also contributing to wholesale regression of media freedom by many states.

In the same vein, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a boon for digital authoritarians, providing them the cover to further strangle already squeezed civic spaces, offline and online, across the continent.

Under the guise of countering COVID-19 disinformation, many African governments have tightened existing social media regulations by further restricting the freedoms of speech, including the media, and association.

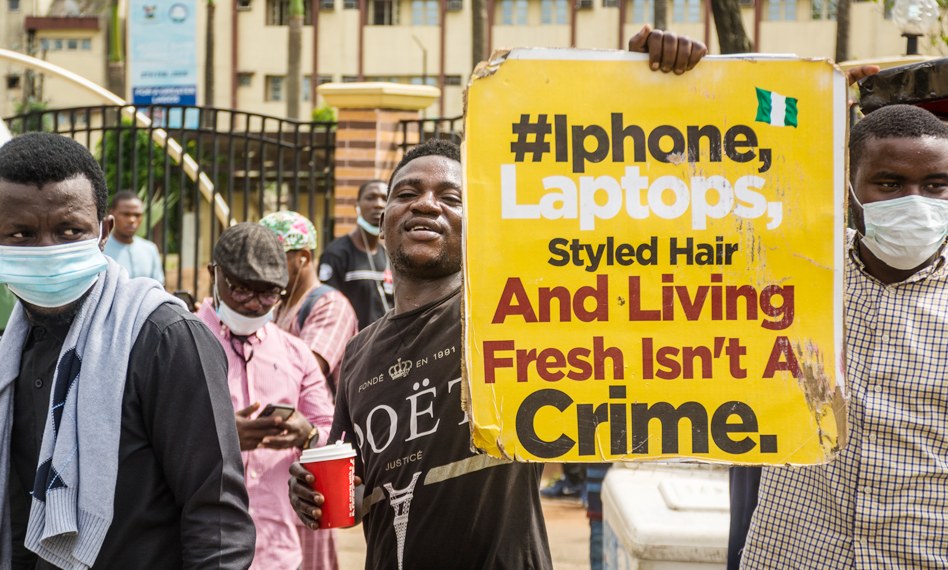

This has led to brutal crackdowns in some cases – the state responses to the primarily youth-sustained #ZimbabweanLivesMatter protest and the #EndSARS movement in Nigeria of 2020 have been illustrative in this regard.

In its 2020 State of Internet Freedom in Africa report, the Uganda-based Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) said: “Several governments enacted vague and overly broad laws and implemented repressive practices that curtailed freedom of expression and restricted access to information through censorship, filtering of content, closure of media houses, threats, arbitrary arrests, illegal detentions, prosecution, intimidation and harassment of journalists, online activists and bloggers.”

However, these oppressive measures have not had the effect of discouraging youth uprisings. Even so, with protests and uprisings rolling on in 2021, and probably beyond, many of these state practices and responses will continue to be rolled out across the continent.

Heavy-handed and repressive social media regulation and invasive surveillance appear to be set to remain features of many African state responses to agitated continental civic spaces for the foreseeable future.

In 2018, then UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, David Kaye, submitted a report on social media regulation and content moderation to the UN Human Rights Council. The report’s main recommendations concerning state actions were:

- States should repeal any law that criminalises or unduly restricts expression, online or offline.

- Smart regulation should be the norm, focused on ensuring transparency and remediation to enable the public to make choices about how and whether to engage in online forums.

- States should only seek to restrict content pursuant to an order by an independent and impartial judicial authority, and in accordance with due process and standards of legality, necessity and legitimacy. States should refrain from imposing disproportionate sanctions, whether heavy fines or imprisonment, on Internet intermediaries, given their significant chill effect on freedom of expression.

- States and intergovernmental organisations should refrain from establishing laws or arrangements that would require the “proactive” monitoring or filtering of content, which is both inconsistent with the right to privacy and likely to amount to pre-publication censorship.

- States should refrain from adopting models of regulation where government agencies, rather than judicial authorities, become the arbiters of lawful expression. They should avoid delegating responsibility to companies as adjudicators of content, which empowers corporate judgment over human rights values to the detriment of users.

- States should publish detailed transparency reports on all content-related requests issued to intermediaries and involve genuine public input in all regulatory considerations.

IMAGE: LAGOS, NIGERIA- OCTOBER 16, 2020: A Nigerian youth holds a protests card during a march against police brutality in Lagos, Nigeria . Photo by Ajibola Fasola, Shutterstock.