New frontiers: Malawian courts set precedent for electoral transparency

In 2020, Malawi punched above its weight to take up an envied position on the global stage, when judges of its Constitutional Court nullified the presidential election of the previous year, 2019, that had seen the re-election of President Peter Mutharika.

It was only the third time on the continent that a presidential election had been overturned by the courts – with the first instance recorded in Ivory Coast in 2010 and in 2017 in Kenya.

The added support by the Supreme Court in upholding the Constitutional Court’s decision to nullify the country’s presidential elections, paved the way for a fresh presidential election which was then scheduled for 23 June, 2020.

Following this historic ruling in Malawi, President Mutharika would find himself voted out of office and his nemesis Lazarus Chakwera from the main opposition Malawi Congress Party (MCP), then leading an opposition alliance, being declared the winner.

The majority of Malawians would rejoice at the change of guard that for them promised a different and more hopeful future.

The desire for change had been many years in the making.

Frustrations over crippling poverty, high unemployment and corruption had crystallised into resentment against Mutharika who would be declared winner of the 2019 elections, dubbed ‘Tippexgate’ because of alleged widespread use of the white correctional fluid used to alter results sheets.

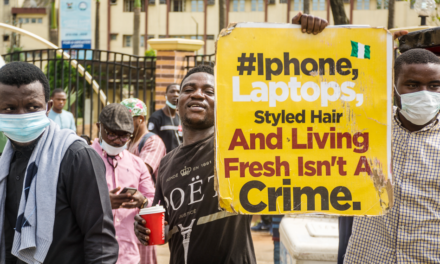

When the country held the fresh elections ordered by the court, villagers channelled their energies into ‘protecting’ their votes, sleeping at polling centers to monitor vote counting, to avoid a repeat of the ‘Tippex elections’.

The court ruling and the ordering of a new election was not just a victory for sensible politics – it was the story of Malawi’s triumph against the abuse of power in one of the most blatant cases of electoral fraud. It was also the story of harnessing of citizen voices by civil society into action. Regular protests over a six month period, with citizens braving threats, beatings, arrests and teargas characterised this period. It was victory for media, both old and new, which had reported on the impasse incessantly and professionally

It is a story that brings together the various elements that contributed to the change – the independence of institutions – in this case both the judiciary and the military, the collaborative pulling together of civil society, the courage of the opposition to oppose the results, the pressure to form a coalition, the harnessing of citizen voices and most importantly the role of the Fourth Estate in telling the story.

The pressure that was being exerted on the judiciary – particularly the five judges presiding over the case by President Mutharika and other players – was high. On a regular basis, Mutharika questioned the validity of the court trial and threatened not to comply with a negative judgement. Shortly before they delivered the landmark ruling, the judges announced they had lodged a complaint with anti-corruption authorities that they had been approached by a rich businessman with the offer of bribes.

But the judges found comfort in the security of the army which safeguarded them as they travelled to various locations with armed escorts to ensure their safety. They also coerced them to wear bulletproof vests.

In the end, their courage and determination was a culmination of painstaking work of building strong institutions, many years in the making. Above all, it was a product of a citizenry both active and ready to defend their rights and freedoms and their cherished democracy.

As a consequence for standing up for their rights, those involved paid a hefty price.

One town in particular bears the scars of its involvement in the struggle for good governance and election justice. Nsundwe Trading Centre, just outside the capital, Lilongwe, despite being a then opposition MCP stronghold, had no previous history of being a hotbed for political activity which it became in 2019.

“Some of the survivors were raped right in the presence of their children, some of whom are able to recount the incidents and describe the police officer’s penis in great detail,” the Malawi Human Rights Commission, a state funded constitutional body, reported after investigations.

The town—not far from the birthplace of President Lazarus Chakwera—became a no-go zone for the ruling party and police, but the town’s notoriety would be enhanced by the bussing of its youths into the capital city for every protest. Scores of buses and pick-up trucks would arrive just before each protest with youths that would confront the trigger-happy police but who would also loot innocent shops, earning the nickname, the Nsundwe garrison.

In the pre and post-election period independent media was under immense duress. But it, too, stood up to be counted when it mattered.

In that period of turmoil, I was one of those arrested, spending hours in police custody alongside two other journalists after being arrested at the airport while covering the arrival of an election observer mission from the European Union. It turned out to be a challenging period for journalists and media houses. Regularly, journalists were assaulted and harassed for doing their job.

The police were biased and antagonistic towards the people, but the army generals firmly stood by the constitution. After the court verdict, Mutharika fired both the military chief and Chief Justice, hoping to instill fear in the army and among judges. But he failed in both attempts.

The Supreme Court shortly afterwards affirmed the decision of the Constitutional Court after lawyers at home and further afield came together to defend the Chief Justice and a senior judge from forced retirement by, among others, holding street protests and obtaining a court injunction.

The dismissal of the popular head of Malawi Defense Forces, General Vincent Nundwe was not followed by a change in the military’s non-partisan stance. (Nundwe was later re-appointed as Commander when the opposition swept to power).

For a journalist like me, covering the impasse, it was illuminating to watch my country’s democratic institutions standing up to be counted, and the citizenry themselves refusing to accept the negation of their freedoms and aspirations for convenience of a few ruling elites.

I saw the determination of the people to ensure the country’s destiny was not mortgaged, not only among the rich and educated in cities, but in the countryside, where for the first time in the country’s history, spontaneous protests had erupted in villages and small towns without a previous history of political activism.