Africa’s citizens fight back

Unpacking the ECOWAS court ruling on Togo’s internet shutdown

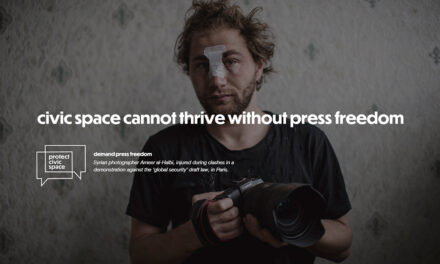

In an attempt to tighten their grip on dwindling power during moments of political crisis, some African governments revert to their default setting of shutting down the internet. In 2020 alone there were a total of 18 internet blackouts in 10 countries on the African continent. Three months into 2021, there have already been four shutdowns. In Togo a woman journalist and seven rights organisations put up a regional legal challenge. Victor Mabutho spoke to the applicants and legal and digital rights experts to get an understanding of the impact of the historical challenge and subsequent judgement.

When on 25 June 2020, the Economic Community of West African States Community Court of Justice (ECOWAS CCJ) handed down its historic ruling that Togo’s 2017 internet shutdowns were illegal and violated citizens’ rights, the news reverberated around the world.

“The shutting down of internet access by the Respondent state of Togo violated the rights of the Applicants to freedom of expression,” read the court’s binding decision. It pointed out that Togo had failed to prove that it had a law in place to justify switching off the internet.

The Togo government had shut down the internet twice during September 2017, claiming that it’s Law on the Information Society and the Law of 2011.27 were in place to justify the shutdowns.

The court directed the government to formulate laws respecting citizens’ right to freedom of expression and access to information in line with international human rights standards such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR).

The CCJ went on to award financial compensation to each applicant.

The legal challenge against the government was brought to the West African regional court by woman journalist, Fabbi Kouassi and seven Togolese organisations, Amnesty International Togo, L’institut Des Medias Pour La Democratie Et Les Droit De L’homme, La Lantere, Action Des Crechretiens Pour L’abolition De La Torture, Association Des Victim De Tortur Au Togo, Ligue Des Consommateurs De Togo and L’association Togolaise Pour L’education Aux Droits De L’homme Et La Democratie.

The historical judgement placed the right to freedom of expression at centre stage and as the first court challenge on internet shutdowns at international level, it set a precedent, not just on the African continent but globally too.

The media and digital rights lawyer who represented the applicants, Mojirayo Ogunlana-Nkanga, while happy with the decision, said the court could have expanded its judgment to say everyone has the right to access the internet.

Electronic communications law consultant Justine Limpitlaw, welcomed the ruling but said: “it’s not the finish line”. She said it was an important starting point as it set a precedent for the ECOWAS CCJ. It would also be of persuasive value across the continent. “People will look at its very careful articulation of why access to the internet is a corollary right of freedom of expression,” she added.

Limpitlaw sees governments being pressed into creating laws which justify the curtailing of freedom of expression. She predicts that in the future, the internet shutdown cases that are brought before the courts will focus on whether the law used to implement shutdowns is in line with international protocols.

The political crisis that led to Togo’s internet shutdown in September 2017, was sparked by a stand-off between the opposition and government on constitutional amendments. The government-enforced internet blackout occurred against the backdrop of deadly violence unleashed by security forces who assaulted and teargassed opposition demonstrators.

Kouassi, who had been covering these protests, was incensed by the State’s heavy-handed response to citizens demanding presidential term limits and so she decided to take action

The frustration which she and many Togolese citizens experienced, was underpinned by the submission made by the former United Nation’s Special Rapporteur to the Right of Freedom of Opinion and Expression, Professor David Kaye, in his application as a friend of the court.

Outlining the detrimental effect of shutdowns, Kaye pointed out, among others, that shutdowns damage people’s access to information and also their access to basic services. Vulnerable groups, he added, such as those with disabilities, women and racial minorities often depended on critical online resources. Businesses reliant on electronic transactions were particularly affected, he added.

Deprived of her right to work as a journalist, Kouassi joined forces with Amnesty International Togo (AIT). ‘We decided to challenge the government, but instead of using local courts, we decided to approach the ECOWAS CCJ based in Abuja, Nigeria’.

The case was filed with the regional court in Abuja in December 2018 which had its first sitting in February 2019. An attempt to get it dismissed on the grounds that the seven organisations, save for Kouassi, were not individuals, failed. The Togo government had interpreted the rules as only allowing persons who are victims to stand before the court and not organisations. The court in turn allowed the seven organisations to represent those violated by the internet shutdown after they proved their interests in protecting freedom of expression.

Along with Kaye, expert submissions were also made by several civic and digital rights groups such as Access Now and Article 19 in their capacity as ‘friends of the court’, in support of the applicants’ suit.

Executive director of Media Rights Agenda, Edetean Ojo, drew a link between this court ruling and decades of lobbying which has created the current legal framework that protects media rights and freedom of expression.

“One can confidently say that the judgment … is evidence of the continually evolving long-term vision of the Windhoek Declaration (adopted in 1991) on the need for the establishment, maintenance and fostering of an independent, pluralistic and free media environment in Africa, that is essential to the development and maintenance of democracy and for economic development,” said Ojo.

The then African Commission Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information, Lawrence Mute, pointed out that the internet had empowered African people with a voice, and urged government not to take that voice from them.

A year since the judgment has been passed, the Togo government is yet to fulfil the requirements of the ECOWAS CCJ’s ruling.

“There is the issue of enforcement of judgments. ECOWAS (regional bloc) is not sanctioning countries such as Togo which have not complied with regional court decisions,” points out Ogunlana-Nkanga who says punitive regional consequences could stop governments from shutting down the internet.

Limpitlaw points out that if African governments want to attract investment, the pragmatic approach would be to adopt a softer stance on human rights and freedoms. “Investors really take a very hard look at human rights issues, particularly on freedom of expression, because it impacts their own ability to do business.”