Fact-checking: Pushing back on disinformation

While social media laws and regulations look inviting, they are ineffective and counterproductive in dealing with false information. Fact-checking, coupled with media and digital literacy, remains the best strategy to fight information pollution. For democracies, this could mean better choices, better leaders, responsive policies, and more honest public debates in the media.

Disinformation—the deliberate sharing of false information to cause harm— is an old problem that has gotten new wings to fly, thanks to the ubiquity of social media at a time of rising political polarisation in many countries in Africa.

Thirty years ago, when the Windhoek Declaration was signed, very little was known about the internet’s value to the media in Africa as social media was non-existent. The continent’s media landscape was more concerned about the promise of liberal democracy and the threats to the press posed by the opposing forces from the dozens of authoritarian governments, enduring neo-colonial policies, and fledgeling development indicators.

A lot has changed since. Recent data from the World Bank shows that the number of people using the internet in Sub-Saharan Africa has grown to an estimated 25% of the continent’s population. The current global average of individuals using the internet is 51%. In 1991 internet users in the continent and across the world were too few to statistically matter, but recent data shows that Africa’s connected people are way below the global average. Nearly two-thirds of Africa’s adult population is considered literate, from 52% in 1991. At a global level, this number is 86%.

From a democratic perspective, dozens of dictators have fallen to popular uprisings thanks in part to the mobilising role of social media. However, one thing has not changed: how public figures and governments construe the salient power of information. The media’s supremacy in shaping opinions and influencing people remains intact.

The exponential explosion of social media use over the last decade has complicated the information ecosystem. It has given rise to citizen journalists, bloggers, influencers but also to merchants of false information. A lot of information that used to be paid for is now available cheaply, and in some cases for free.

In most African countries, with low media and digital literacy rates, false information, fabricated content, political propaganda, and hate speech, has become everyday ado, spreading like wildfire, polluting the information ecosystem and causing real harm and posing danger in society. Examples abound, including xenophobic attacks in South Africa in 2018, the manipulation of elections in Kenya (2017) and Nigeria (2015) by British firm Cambridge Analytica, and even the government-run information operation in covering up human rights abuses in Ethiopia, styled as the “Ethiopia State of Emergency Factcheck”, currently ongoing.

In the times of the COVID-19 pandemic, false information has caused panic, deaths, and sickness in different parts of the continent. Some people tried out unproven remedies or rejected conventional medicine favouring miracle cures and healthy diets with rumoured curative properties – as spread through the information interwebs. Increasingly, others have lost livelihoods to scammers and fraudsters.

For many governments on the continent, the response to disinformation on social media has been the cudgel of legislation – activating old media laws on libel, defamation and security, and enacting new ones to punish the creators and purveyors of false information in cyberspace. Other governments have made access to social media expensive by introducing tax for those who want to access the platforms. Still, others have deployed near-Orwellian digital surveillance of their people, arresting those who say things those in power do not like, and censoring those who cannot be detained and amplifying the fawning sycophancy of supporters.

The borderless nature of the internet, the sheer number of users, the intrinsic sociality, community, and collaboration embedded in the architecture of social media platforms, plus the premium on fundamental freedoms of the media and expression, have complicated the information management calculus – the political and policy considerations on the implications of releasing or withholding information– for most governments. Regardless, it is unlikely that governments will depart from what they know best –using the law, force and prison to hide the truth, and if they can’t do that, to openly mislead the public..

Some governments have resorted to shutting down the internet, consequently shutting down the economy, while others ban social media, which has led to mostly young people organising offline and bringing governments down. New punitive laws that limit fundamental freedoms cause resistance, protests and litigation. It is difficult for people to trust historically unreliable governments to be the arbiters of truth.

But there’s another way to deal with information pollution: Fact-checking.

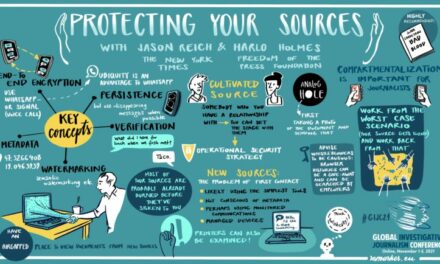

Fact-checking is about verifying information, seeking proof, getting the most recent data, speaking to subject-matter experts for context, and finally sharing the facts accurately. It is a replicable, transparent process using the most recent publicly available information to sort facts from fiction. As Africa Check, the continent’s leading fact-checking organisation, puts it, “It is not a name-and-shame adventure. It is about keeping the public debate honest”.

The theory behind fact-checking is the neat explanation that if people have access to credible and accurate information, they will make decisions based on reality and, therefore, get pragmatic solutions to their problems. For democracies, this could mean better choices, better leaders, responsive policies, and more honest public debates.

It is however, foolhardy to expect governments in African countries, many of the perpetrators of disinformation, to invest time and resources in fact-checking.

It has been expected that journalists would do fact-checking, but the political economy of the media in Africa makes this difficult because of the political parallelism in media ownership and operations. In some countries, politicians own media houses or belong to the same tight elite circles as media owners. In nearly all countries, politicians are the primary news sources. At a time when the digital disruption has reduced media revenues, the investment and independence required for a credible fact-checking operation is not a priority for many media enterprises.

This leaves independent actors in civil society, supported by donors, or some running for-profit projects or collaborating with social media platforms to limit the circulation of false information. For fact-checkers like Africa Check, the priority is in debunking false information, circulating the correct information as widely as possible, pointing people to credible sources of information, and carrying out media and digital literacy clinics to ensure more people in Africa have the knowledge and skills to verify information on their own using open-source tools. This is not an easy exercise, however, the goal is to break the cycle of false information.

Fact-checking allows the correct information to compete with the false information without limiting the freedom of expression of those who may be misinformed or those doing the mis-disinformation. While false information may go viral, thereby travelling far and wide quickly, having a critical mass of people with digital and media literacy skills helps break the cycle and slow down the information pollution.

At this point, we believe that fact-checking and media and digital literacy will ensure the aspirations of the Windhoek Declaration – for “the widest possible range of opinion within the community” to be reflected in the public sphere— are achieved in today’s digital world.

For now, the threat to pluralism and true freedom of the press and people, are digital censorship, government-sponsored disinformation campaigns, and surveillance with punitive goals, which remain more potent threats to the fulfilment of human aspirations for free expression, access to information and freedom of assembly through social media.